The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals Agenda 2030 (reference) as well as the Aichi targets of the Convention on Biological Diversity (reference) recognize the need to safeguard marine ecosystems for sustainable development and to eradicate world poverty. The value in the world economy of services attributed to marine ecosystems is estimated at around USD 28 trillion (reference).

Therefore, the sustainable use and conservation of coastal marine ecosystems and their biodiversity have become essential along the road to Agenda 2030: both the Sustainable Development Goal # 14 and the Aichi Target # 11 recommend the protection of the 10% of the marine areas of the member countries.

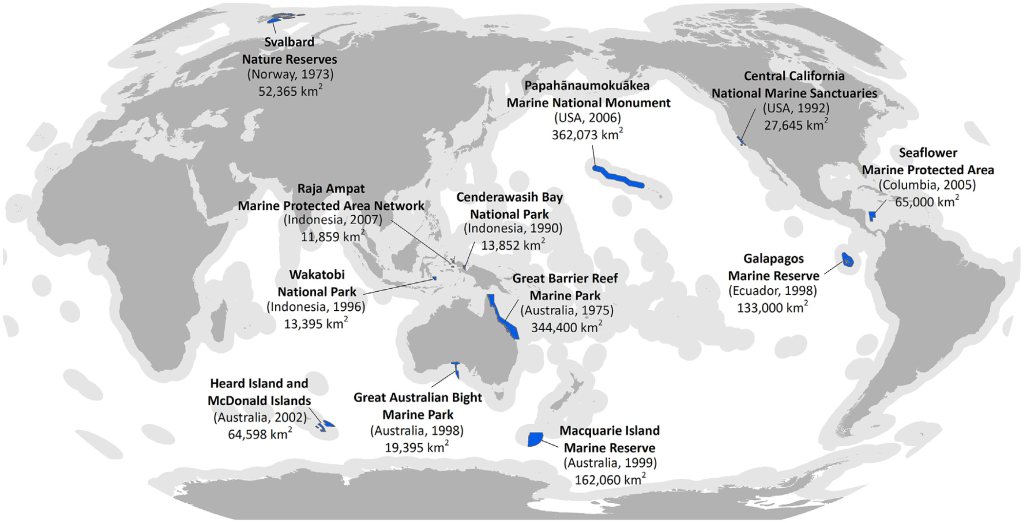

Increased commitments to the protection of the oceans and the achievement of United Nations goals have favored the creation of Large to Very Large Marine Protected Areas (GAMP), some of them exceeding one million km2 (Boonzaier and Pauly, 2016).

Some of the World’s Largest Marine Protected Areas ( Ban et al., 2017)

In his last year as president, Barack Obama doubled the existing protected surface area of the United States and expanded the already large Papahānaumokuākea AMP to 1,510,000 km2, protecting coral reefs, deep habitats and very important ecological resources in the northwest of the islands of Hawaii (reference) . Shortly afterwards, Russia declared the AMP of the Franz Josef Land islands chain, protecting approximately 100,000km2 of pristine ecosystems in the Russian Arctic (reference). The European Union was not far behind protecting the Ross Sea in Antarctica from the pressures of industrial fisheries for a period of 35 years (reference). Australia, with 36% of its exclusive economic zone under some protection scheme (of which 13% are non-fishing zones) is one of the world leaders in marine protection. Its network of MPAs ranging from the Great Barrier Reef to the sub Antarctic island Macquarie is one of the oldest, with the first area declared 130 years ago (reference).

The Thirteenth Meeting of the Convention on Biological Diversity: COP 13 was convened in Cancun in early December 2016. COP 13 focused on “Integrating Biodiversity for Welfare”, over 10,000 participants worked by sharing knowledge and negotiating agreements and Commitments for the achievement of the Aichi Targets.

The host country, Mexico, is one of the most diverse countries on the planet; its natural heritage is the root of its cultural wealth and a source of opportunities for its communities. These characteristics make Mexico and Cancun in particular, a suitable place to undertake ambitious programs and take firm positions.

As a sign of his commitment to protect the world’s natural heritage and contribute to the achievement of the Aichi goals, the President of Mexico, Enrique Peña Nieto, declared the creation of four new natural protected areas totaling 650,000 km2, equivalent to 23% of Mexican seas (reference). Among them, the Mexican Caribbean Biosphere Reserve.

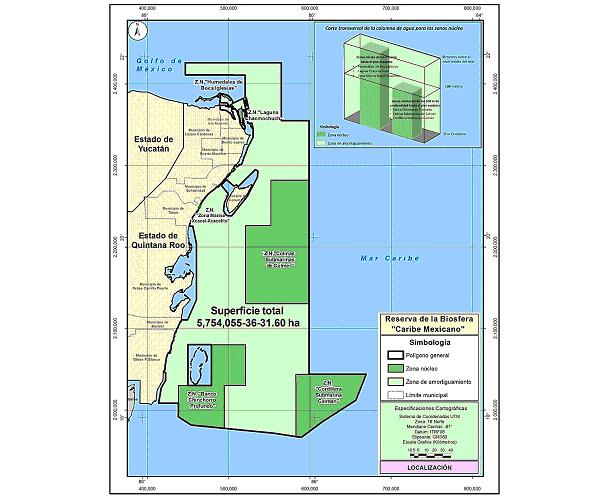

The Mexican Caribbean Biosphere Reserve, was hence decreed on December 7th, 2016. It is located in the State of Quintana Roo, with an area of 57,540 km2 (equivalent to the surface of the state of Campeche), of which 57,250 km2 correspond to the marine portion including reef zones, deep seabed and coastal lagoons; and 286 km2 correspond to the wetlands and coastal zones. This makes it one of the largest MPAs in Mexico and accounts for 50% of the Mesoamerican Reef (MAR).

According to its decree (DOF, 2016), the area has six core zones: Boca Iglesias Wetlands, Chacmochuch Lagoon, Xcacel-Xcacelito Marine Zone, Chinchorro Deep Bank, Colmer Submarine Hills and Cayman Submarine Ridge with a total area of 19,330 km2. It is worth mentioning that the territory covered by this Reserve borders 14 protected natural areas of federal character, which retain their decrees, conservation objectives and management plans in cases where they already exist.

Map of the Mexican Caribbean Biosphere Reserve (DOF, 2016).

According to the study that justified the creation of the reserve (EPJ, 2016), its purpose is to respect not only the natural interaction between them, but also to favor the continuity of conservation and sustainable use efforts that have been carried out to date in the area. It seeks to harmonize the development of anthropogenic activities in a way that promotes connectivity, displacement and development of the species that inhabit it.

Among its main conservation objectives are:

- Preservation of terrestrial and marine ecosystems,

- Conservation of lagoons and wetlands,

- Conservation of turtle beaches,

- Protection of deep areas of the Caribbean, and

- Total prohibition on exploration and exploitation of hydrocarbons.

In the core areas of the Reserve it will be possible to carry out tourist activities, nautical tourism, navigation of boats in transit, and non-extractive exploitation of wildlife. The most important points in the core zone are the explicit prohibition of fishing activity or extractive exploitation of flora and fauna, mining exploration and extraction and extraction of stone material, sand extraction, and the use of trawling methods or invasive techniques on the seabed. In buffer zones certain activities will be permitted under strict restrictions such as fishing and aquaculture, construction of port infrastructure and support for tourism and research, sand extraction, boat navigation, and installation of artificial reefs, among others.

Although the operation and management of the ANP is carried out by the National Commission for Natural Protected Areas (CONANP), the inspection and monitoring is carried out by the Secretariats of Marine (SEMAR), Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT), through the Federal Office for Environmental Protection (PROFEPA), and Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food (SAGARPA).

Natalie Ban and collaborators have identified several factors affecting the effectiveness of large marine protected areas around the world. They concluded that social wellbeing of communities and ecological performance are directly linked to stakeholder participation and high levels of enforcement (Ban et al., 2017).

Park ranger during control and monitoring patrol. ( Photo: María del Carmen García)

Park ranger during control and monitoring patrol. ( Photo: María del Carmen García)

Precisely, the operation and management of its 57,540 km2 represent one of the biggest challenges facing the new reserve. With a 37% annual budget cut between 2016 and 2017, recent staffing adjustments and a financial gap of 560 million pesos by 2017, CONANP faces the difficult challenge of effectively managing a growing area. Particularly, for the Mexican Caribbean Biosphere Reserve, there is concern about the economic viability of the project, as well as its administrative and collection architecture. In this sense, the reserve is currently facing the challenge of how to organize, disseminate and disseminate information on these aspects, as well as how to be more creative in the incorporation of new participatory resource mobilization schemes (Llano and Fernández, 2017) .

On the other hand, the threats to which the object of conservation of the reserve is also facing are increasing. According to a study of tourism activity in Quintana Roo presented in 2017, Cancún in 2016 achieved a hotel occupancy of 80.4 percent and increased its tourist influx by 3 percent to close with 4.7 million visitors, while the Riviera Maya exceeded 80 percentage points of occupancy for the third consecutive year and grew its housing offer by 10.3 percent. Only Cancún ended 2016 with 32,432 hotel rooms, which brings growing pressure from the growing area, associated with logistical challenges such as how to guarantee access to the state’s drinking water, or how to feed an estimated additional population Of 329,886 inhabitants by 2040. What will be the impact of the new reserve on Urban Development Plans and Ecological Planning Programs to ensure the quality of their ecosystems is still an issue to be defined.

Finally, there is uncertainty as to the lack of guarantees regarding the date of publication of the reserve management program. With such notorious precedents as the case of the APFF Yum Balam or the lack of updating of the Arrecifes of Puerto Morelos, the subject is a hot stone because in the decree of the reservation textually it is mentioned that the existing zoning will be respected. The management programs of the ANPs and the corresponding advisory councils facilitate the dialogue with the inhabitants and the users of the ANPs, give certainty about the activities allowed, regulated and prohibited. However in 2017, 79 federal ANPs do not have management programs and 94 do not have advisory council (Llano and Fernandez, 2017).

Even though the challenges are great, we have the opportunity to mobilize resources to our country to help manage NPAs, as some nations, such as Germany, have offered millions of euros to support the creation of new NPAs worldwide. It also represents an opportunity to change from business as usual, learn and effectively organize human, monetary, and strategic resources to accomplish the objectives of our new reserve in the Mesoamerican Reef System.

Kids playing in Holbox island. (Photo: Jeronimo Aviles Olguin)

References

- Ban N.C., Davies T.E., Aguilera S.E., Brooks ., Cox M., Epstein G., Evans L.S., Maxwell S.M. and M. Nenadovic. 2017. Social and ecological effectiveness of large marine protected areas. Global Environmental Change, 43, 82-91.

- Boonzaier Lisa and Daniel Pauly.2015. Marine Protection Targets: an updated assessment of global progress. Oryx, Fauna & Flora International, 50 (1), 27-35.

- Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas. 2016. Estudio Previo Justificativo para la declaratoria de la Reserva de la Biosfera Caribe Mexicano, Quintana Roo. 305 páginas. Incluyendo tres anexos.

- DOF (2016). DECRETO por el que se declara Área Natural Protegida, con el carácter de reserva de la biosfera, la región conocida como Caribe Mexicano. 07 de diciembre de 2016. Disponible en: http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5464450&fecha=07/12/2016

- Llano Manuel and Humberto Fernández (comps). 2017. Análisis y propuestas para la conservación de la biodiversidad en México 1995-2017. Ciudad de México, 120 pp.